Filtered permeability: The most effective way to achieve Better Streets?

Coronation property proposal and an artist’s impression of modal filter/public square on MacDonald St, Erskineville – created using Gemini AI and Photoshop.

Why are we still being sold images of car-dominated streets, when what most people want is a neighbourhood that feels welcoming, calm and easy to move around in?

Across the world — and increasingly in Australia — communities are showing that it’s entirely possible to create low-traffic neighbourhoods where walking and riding are safe, convenient and enjoyable for people of all ages.

One of the simplest and most effective ways to achieve this is through a concept known as filtered permeability.

Figure 1 - Filtered permeability in London, UK. Source: Transport for London https://madeby.tfl.gov.uk/2020/12/15/low-traffic-neighbourhoods/.

Filtered permeability – restricting through motor vehicle traffic while allowing permeability for people walking and riding a bike – is arguably one of the most powerful ways of creating Better Streets.

As well as blocking through traffic (rat-running), it reduces the attractiveness of driving for short, local trips, but does not prevent access (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Driving versus walking or cycling for a local trip in Houten, the Netherlands. Houten is a prominent example of filtered permeability in urban planning, where the street network is specifically designed to allow pedestrians and cyclists to travel more directly than motorists. Driving in Houten is less attractive, but still possible when necessary.

These two mechanisms combine to significantly reduce traffic volumes, resulting in quiet, people-friendly streets with cleaner air. With less vehicle traffic, walking and riding a bike return to being safe and attractive. Add mixed-use development and good public transport, and residents can easily access jobs, education, shops, services and other activities (which is the ultimate purpose of transport) – not just those who can drive and afford a car. Children can get around independently.

Despite the many benefits, the implementation costs can be very low. And with less traffic, the need for infrastructure like bicycle paths and traffic signals may be reduced.

Filtered permeability is often achieved using strategically placed “modal filters”: bollards, garden beds, pocket parks or similar that restrict through traffic while maintaining local access. See this Ranty Highwayman blog post for some examples. Turning and one-way restrictions can also be used. Exemptions can be made for emergency vehicles, buses and garbage trucks, if necessary.

A modal filter can be installed on a single street to deal with a problematic rat run. But this may move the problem elsewhere. Ideally, filtered permeability should be applied to a neighbourhood, or even a whole town or suburb.

It is easy to implement in a greenfield development. However, retrofitting existing neighbourhoods can face opposition from residents accustomed to driving for short, local trips – because it could mean a few extra minutes of driving, or changing their travel choices. And, in a motonormative society, there may be some who simply value traffic more than pleasant streets, clean air, and children's safety. To address these concerns, filtered permeability can be trialled using temporary traffic treatments. Opposition will often subside once residents see the benefits.

Filtered permeability is the norm in countries like the Netherlands, where it was a central part of the government response to the 1970s Stop de Kindermoord (Stop the Child Killing) movement. It has also been adopted in cities as far-flung as Barcelona (Superblocks), London (Low Traffic Neighbourhoods), Seoul, and Vancouver.

However, adoption in Australia has been slow. One success story can be found in Newtown and Erskineville in Sydney’s Inner South. In response to increasing through traffic and pedestrian injuries in the 1980s, residents campaigned for the rat runs along their narrow streets to be blocked. Despite opposition from the state government, they won, and the council installed several modal filters. Many of these were later upgraded to pocket parks (Figure 3). The TV news reports from the time are well worth a watch.

Figure 3 A modal filter in Newtown, NSW. (Google map location)

Thanks to these residents, and despite significant population growth in the years since, these streets are still quiet and relatively safe today. A recent travel survey for the local primary school found that about three quarters of students usually walk or ride, which is extraordinary by Australian standards.

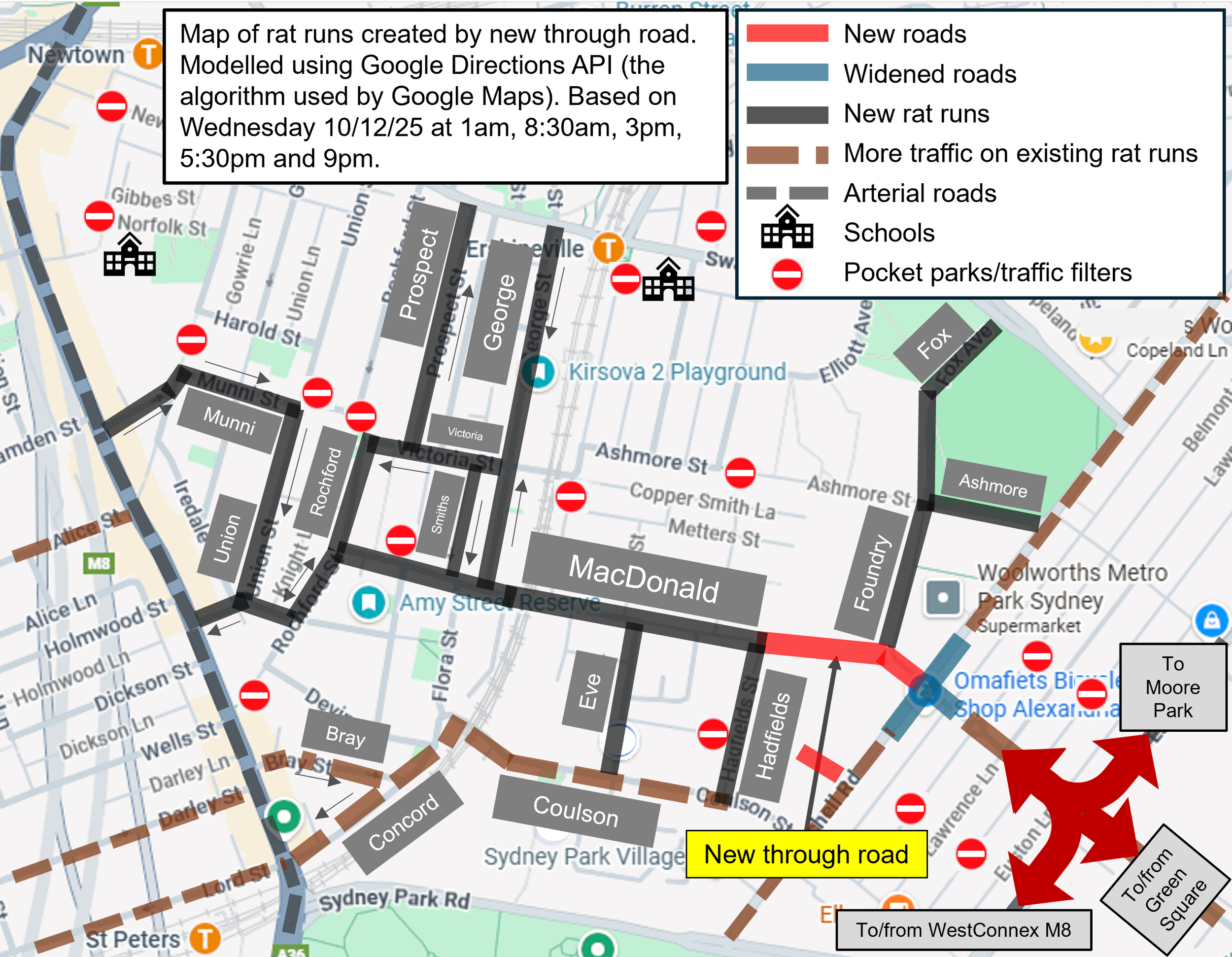

Sadly, a property developer, Coronation Property, is now planning to build a new road that will reopen many of these streets to through traffic (Figure 4). Inexplicably, Sydney’s Lord Mayor, Clover Moore, who supported the 1980s campaign and has done so much to create Better Streets in Sydney’s CBD, is siding with the developer and the roads lobby – claiming that the new road will “help new residents of Ashmore get to and from their homes by car”. In fact, residents would still be able to access their homes by car without this new road.

Figure 4: How a proposed new road would reopen local streets in Newtown and Erskineville to through traffic.

At a recent event to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the successful 1980s campaign, Friends of Erskineville launched a petition calling for a public square to be created in place of the proposed new road. This is a great example of positive advocacy: not only demanding quieter and safer streets, but also much-needed public space and greenery in a densifying suburb. Over ten thousand letters have been sent so far. See more details here: petition .

Could filtered permeability deliver Better Streets in your neighbourhood?

If you want to advocate for filtered permeability in your neighbourhood, below are some lessons from the past and current campaigns in Newtown and Erskineville.

Build a coalition with existing resident action groups, school P&C associations, and business groups.

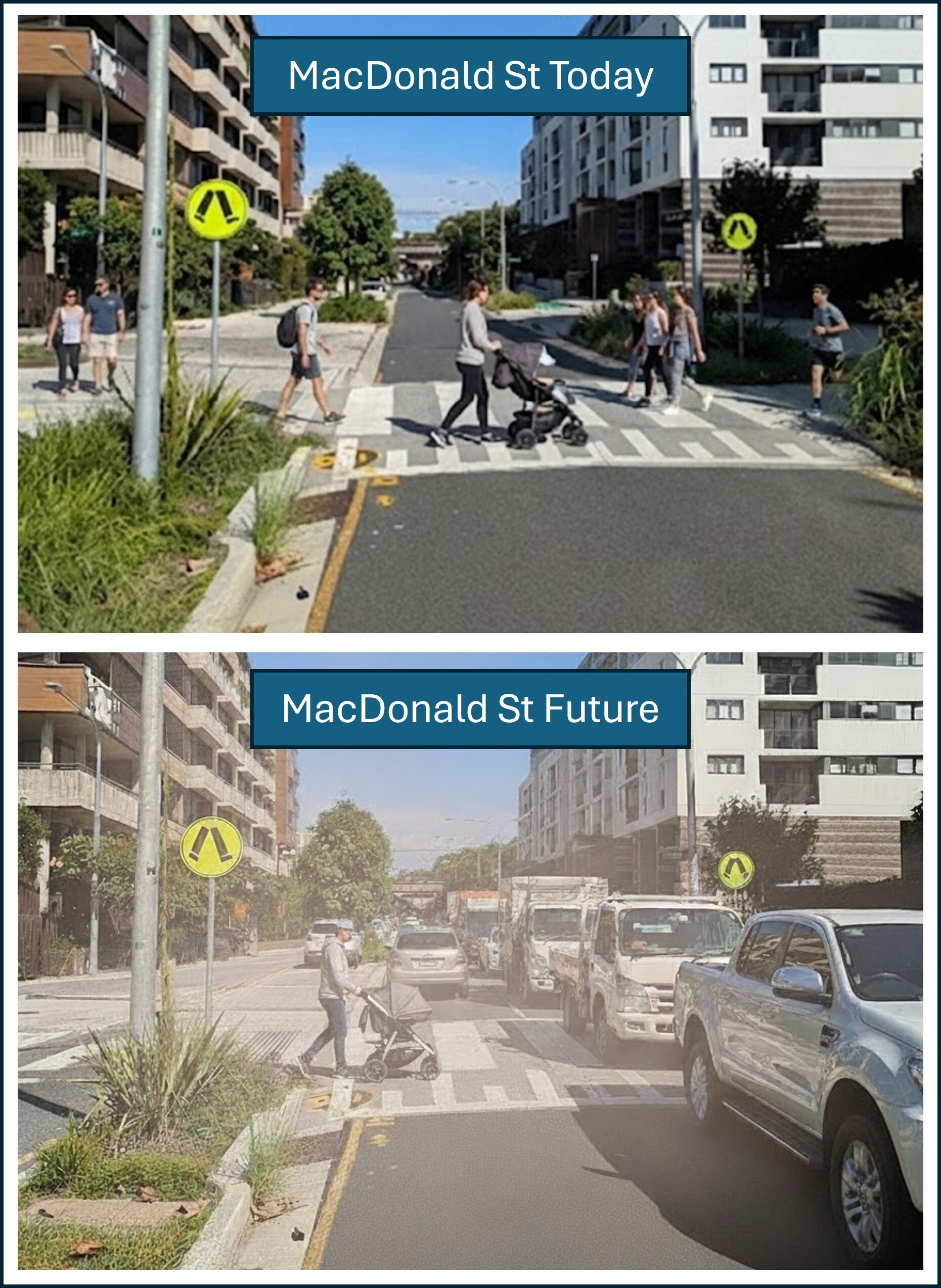

Use visuals to show how streets could look with less traffic and more people, trees and public space. See Figures 6 below for examples, and this Better Streets resource for tips on using AI image editing.

Use positive language, for example: public space, trees, safe, quiet, clean air, and access.

Start a petition or letter-writing campaign. See here for an example.

Promote your campaign using social media (including platforms used by diverse age groups), flyers and posters.

Contact councillors directly. A phone call is usually more effective than an email.

Encourage children to write personal letters to councillors.

Prepare evidence-based rebuttals to common objections and misconceptions. See here for an example.

Get local businesses on board. They may benefit from increased footfall or opportunities for outdoor dining.

Join the Better Streets movement. It provides valuable connections and resources.

Direct action can be effective in getting media attention.

Figure 5: Artist’s impression of MacDonald St, Erskineville, with and without through traffic – created using Gemini AI.

Article written by Dr Chris Standen, a research fellow in urban development and lecturer in transport planning at the University of NSW. https://www.unsw.edu.au/staff/christopher-standen